Do kids need special protections or do we all need them?

This post is a work in progress and subject to editing and updates

by Larry Magid

We have always taken child safety more seriously than adult safety, even where children are not necessarily at greater risk than adults. It’s probably instinctual. As every parent knows, protecting one’s offspring is not something we even have to think about. We just do it.

Children not always a special case

But when it comes to risk, children are not always a special case. For example, in California it’s against the law for children under 18 to ride a bicycle without a helmet yet, every year, nearly 17,000 adults are killed or injured in bicycle accidents in the U.S., compared to about 2,200 children. More than 88% of the injured are adults even though adults make up 77% of the population, which means that people over 18 are more likely to be injured than children. I think of this every time I ride my bike through the Stanford University campus near my home and notice all those over-18 people putting their expensively educated brains at risk by legally riding without helmets.

Bullying doesn’t just affect kids

The same can be said of other types of risks. Workplace bullying among adults is higher than school-yard bullying of kids. A 2010 study commissioned by the Workplace Bullying Institute and conducted by Zogby International found that more than a third (35%) “have experienced bullying firsthand.” That’s higher than any of the credible studies of youth bullying. Plenty of adults are also affected by cyberbullying (adults sometimes call it “trolling”) as well.

Why are privacy laws aimed at kids

There are all sorts of existing and proposed privacy laws to “protect” children, yet there is no evidence that kids have any more privacy risks than adults. In fact, adults may have even more privacy risks given what they do online and the potential payback for being able to sell them products based on their online activities. When it comes to government surveillance, nearly all the victims are adults. And from what I’ve been able to observe in social media, adults are not typically more privacy savvy than teens when it comes to what they post. In fact, a 2013 Pew Research survey found that teens are more privacy conscious than many adults give them credit for.

Yet the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) is aimed only at kids under 13 while California’s “eraser button law” affects only people under 18.

COPPA requires “verifiable parental consent” before a child under 13 can provide personally identifiable information (including IP address) to a commercial service. The well meaning law is designed to protect children’s privacy, but it’s unintended consequence is to ban children from social media sites because of the enormous cost, hassle and, ironically, privacy and security risks associated with obtaining that consent. COPPA also discriminates against children who’s parents, for a variety of reasons including limited English-language or technology skills, and fear of government are unable or unwilling to comply with COPPA.

Congrss is considering yet anothr law, The Do Not Track Kids Act (see Anne Collier’s analysis here), that assumes that young people are at a higher risk because “Children and teens lack the cognitive ability to distinguish advertising from program content and to understand that the purpose of advertising is to persuade them, making them unable to activate the defenses on which adults rely,” but that’s lumping together the age range of zero through 17. It may be true of very young children, but I haven’t seen evidence to suggest that teen Internet users fail to understand the difference between advertising and content any more than do adult users.

Rational laws could protect everyone

To the extent that we need new laws to protect privacy, they should be aimed at everyone, regardless of age. Senior citizens need protection, young adults need protection, parents raising families need protection as do workers at every age. We all need greater transparency so that we know (and are able to understand) how our data is being used and we need laws that limit what government can collect or do with data that companies collect.

Failing to see the bigger picture

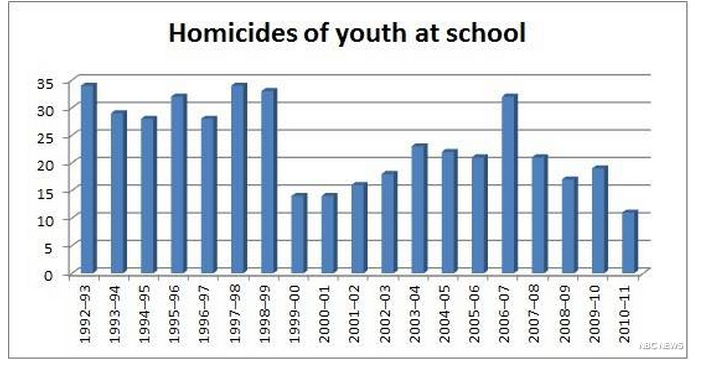

“When we think about kids online or off, we tend to automatically overestimate the dangers, because that’s all we ever see in the media, said Lenore Skanazy, author of the book and blog, Free Range Kids. What’s more she added, “we also don’t see the billions of friendly, helpful or informative chats kids have online daily — only the cyberbullying and sexting. Our fears don’t match reality.” Skanazy is observing the disproportionate amount of media attention on risk to youth. Even the recent incidences of school violence are often interpreted out of context. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics shows a general decline in school related homicides between 1992 and 2011.

Reflecting on the the past 20 or so years, Crimes Against Children Research Center David Finkelhor, in his paper, The Internet, Youth Safety and the Problem of “Juvenoia,” observed an overall positive trend in most youth-related risks including crime victimization, sexual assault and even bullying, causing him to conclude, “Given the convergence of positive indicators regarding children, there is a good chance that we will look back on this era as one of major and widespread amelioration in the social problems affecting children and families.”

Homicides of youths ages 5-18 at U.S. schools, by school year, from the annual report “Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2012,” by the Bureau of Justice Statistics

Children and teens need respect as well as protection

Of course, adults want to keep children safe. But it’s also important to respect them and their rights and to be very thoughtful before using “protection” as an excuse to limit their rights and privileges. Plus, we need to remember that with kids as with adults, one size doesn’t fit all. What’s suitable for a young child may not be suitable for a teen and, even within the same age groups, not all kids are equal when it comes to risk.

Ironically, the adult fear (often irrational) of teen use of social media is, according to author danah boyd, related to our clamping down on their freedoms in the physical world because of parental fears. In her book, It’s Complicated, boyd suggests that “teens simply have fewer places to be together in public than they once did,” which is one of the reasons they flock to social media.

It’s also important to remember that risk is a necessary component of life and an important part of growth and learning for both children and adults. Josie Gleave’s Risk and play: A literature review examines scholarly research in this field, including many studies that suggest that risk-taking is an essential and beneficial aspect of play. She concludes, “There is evidence to suggest that many of the measures that have been taken to crate ‘safer’ play for children are neither necessary nor effective.”